Those who have what it takes to meet the future have curiosity, a fundamental belief in progress, and a desire to make the world a better place. This enterprise requires that our collective knowledge be always increasing, to enable us to continue solving the problems that we encounter. (We need our collective wisdom to increase also, but that is a different problem.) Is it possible for humanity’s collective knowledge to increase indefinitely? Or are there human limitations that we will run into?

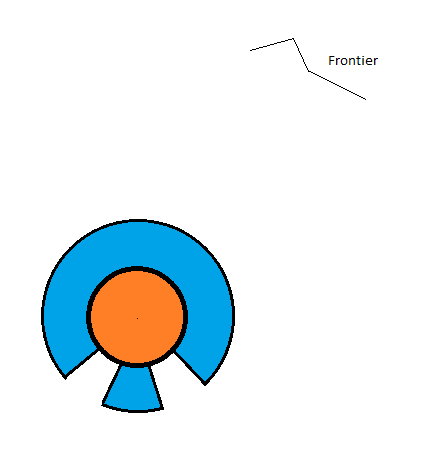

To expand the frontiers of human knowledge, some person or persons have to get there, and then go into new territory. But we all start out life the same, with no knowledge (beyond our instincts, that is). From that point, knowledge always has to build on prior knowledge; each of us is limited by this fundamental fact. Picture then, knowledge, as concentric areas to be covered:

We go through our primary and secondary school years, and (the top students anyway) come out with a somewhat similar depth of general knowledge. Once in high school, there is some specialization, depicted where the blue area does not cover all possible subjects any longer.

We go through our primary and secondary school years, and (the top students anyway) come out with a somewhat similar depth of general knowledge. Once in high school, there is some specialization, depicted where the blue area does not cover all possible subjects any longer.

Of course there are individual differences in ability and curiosity, the willingness to study things of interest outside of school, etc. Those factors make a difference, but we are still limited by the number of hours in a day.

Once in college, we start to specialize more heavily, focusing on our major subject area. A century ago, a person with a college background could hope to push the boundaries of human knowledge. They were not out of reach, for someone who was intelligent and determined.

Today, 4 years of college is considered a bare minimum for many fields of employment, and yet not everyone is able (money aside) to handle the intellectual rigors of college. Additionally, the frontier of human knowledge has moved out considerably:

The need to get to an ever-more-distant frontier in the same amount of time has forced people to specialize more and sooner (or stay in school even longer). (I attempted to make the areas in light blue the same, to emphasize that the intellectual ground covered in the same amount of time is somewhat constant.) So to get to the frontier now means getting less general education, as a tradeoff.

This has implications. First we are seeing more mistakes being published, because researchers are simply not sufficiently cross-educated in some area. A typical example is the physicist or medical researcher who does not have enough background in statistics to properly analyze their own experimental results. They could consult with a statistician, but they may not even realize the need.

Claims to have discovered something novel now get published because neither the researcher nor the reviewers have a broad enough background to recognize a result from a neighboring field. And there is an increase in claims that findings in one field apply to another (such as physicists claiming a result from their field applies to, say, systems theory), where a basic background in the other field would have been sufficient to reveal the finding as a well-known truth in the other field. Reviewers who are sufficiently expert to review new ideas from the frontier of one field cannot be expected to be experts in every other field.

These happenings suggest that we are indeed reaching a point where human limitations are coming into play.

See here for the other issues science is having today.